For those that were looking at your backyard and thinking, ‘I could use some rain’ it looks like Mother Nature may be willing to help you out.

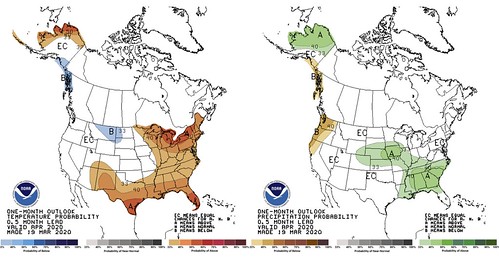

After a long, wet, dreary winter, it looks like the short suspension of precipitation during the last few weeks may come to an end. The Climate Prediction Center, a branch of NOAA that predicts longer-range weather, suggests that April may bring warmer-than-average conditions to the Gulf Coast as well as wetter-than-average conditions.

This time, we can’t blame the MJO.

Matthew Rosencrans, the forecaster for April’s outlook, noted that it won’t play as big a role this April as, perhaps, other months.

“The MJO is forecast to emerge over the Indian Ocean and progress to the Maritime Continent by the beginning of the month,” Rosencrrans wrote. “But the connection from the tropics to the mid-latitude is muted in April, relative to a winter. Forecasts models predict a strong circumpolar flow in the mean, which would also [reduce] tropically teleconnected impacts, so the MJO was considered, but not any significant component for the April outlooks.”

The CPC noted that the precipitation outlook may show above average precipitation, but it isn’t as much a “lock” as it normally may be. That said, the CPC did note that model guidance and trends favor above normal precipitation from the southeast to the Middle Mississippi Valley.

More from the CPC:

Prognostic Discussion for Monthly Outlook

NWS Climate Prediction Center College Park MD

830 AM EDT Thu Mar 19 202030-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR APRIL 2020

The April outlooks for temperature and precipitation reflect the latest model guidance, likely impacts from trends , tropical intraseasonal oscillations, antecedent soil moisture, current and likely snowpack, as well as sea ice near Alaska. Over the western CONUS, the forecast is highly uncertain with initial model output from earlier in the month depicting conflicting signals with more recent runs, and statistical tools depicting weak signals . The increased uncertainty is reflected in the increased coverage of equal chances, compared to many other CPC monthly outlooks.

Model outlooks from the NMME suite reflected generally above normal temperatures, though some models had indications of below normal temperatures in the Northern Rockies and Northern Great Plains. More recent model output has significantly cooler solutions from the West Coast to the Great Plains, with the east remaining warm, so the uncertainty lead to low coverage in the temperature outlook from the West Coast to the Northern and Central Rockies and across the Central Great Plains. Recent dry conditions are not likely to abate in southern Texas, favoring above normal temperatures. Across the eastern CONUS, model outlooks and trends favor above normal temperatures, while anomalously low snowpack (with the exception of areas around the Upper Great Lakes) enhances odds over the Northeast.

Let’s unpack some things

Let’s take a look at the outlooks for cyclogenesis (low pressure formation).

Notice that the CPC only pegs about five to seven areas for cyclogenesis during late March through late April. That lines up with the every 3-to-6 days. So it looks like there may just be an increase in rainfall totals from a normal amount of events.

From that, we can pull out that the CPC expects the storm systems that move through the southeast to have access to more Gulf of Mexico moisture than normal.

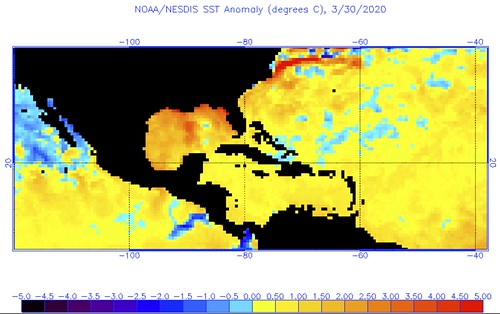

And that, in a way, could be explained pretty quickly. The Gulf of Mexico is running a few degrees above average.

The warmer the Gulf is, the easier it is for passing storm systems to pull water vapor to the north. More water vapor means more clouds. More clouds, more rain.

The flip side to that coin

News no one wants: an increased risk for severe weather.

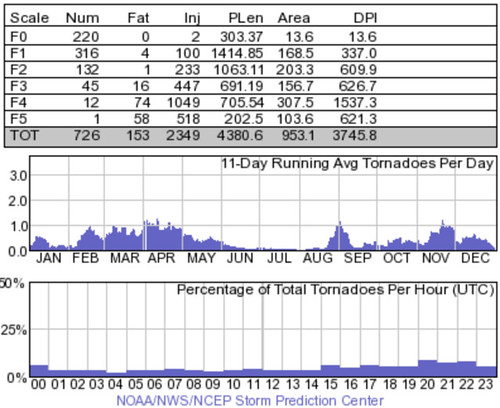

But Nick! April is already the month with the most severe weather! How can we get even more?!

Now, before you start running for the storm shelter now, hang tight because I’m going to try and walk through this explanation and the assumptions it makes and where it can easily fail.

Through past research done by a slew of research meteorologists, a warmer Gulf of Mexico translates to an increased risk for severe weather and tornadoes across parts of the southern plains. I’ve even used that research in the past to create a seasonal tornado forecast. For the Gulf Coast, it gets a bit more difficult to find a connection. Same with the rest of the southeast. But, the bottom line is that the warmer the Gulf is, the easier it can transport that warmth northward with every approaching cold front. That is Assumption One.

Assumption Two is based on the CPC’s outlook that shows higher than average soil moisture across parts of the Great Plains. This would lead to colder air from CAnada being modified slightly quicker as is pile drives south behind cold fronts. If the air is modifying a bit faster, it means the temperature gradient – and thus the pressure gradient – would be as pronounced. This could help to dampen the intensity of cold fronts slightly. That would, also, lead to a decreased intensity of low pressure systems. That is Assumption Two.

Assumption Three goes to southwest Texas where it has been drier than average and warmer than average. That could lead to an increased chance that the dry line would mix further east. Especially if soil moisture across parts of south central texas is also low. A further-east-mixing dry line would also increase the risk for severe weather across parts – but not all – of the Gulf Coast. That is Assumption Three.

Two for, one against.

The last point I’ll add, isn’t an assumption, more of a curiosity. During the past few weeks the storm track within the models, for the Day 4 through Day 10, hasn’t been handled well. I’m not sure why, I’m not a weather modeller person. But the current storm track still a bit split. And this isn’t strange, really. Usually during the winter storm systems form in Texas, or into the Gulf, and scrap through the Gulf Coast. Other storm systems drop out of Colorado and move to the NE through the Great Lakes.

What will be interesting to watch is when the southern fetch of storm systems (the ones along or near the coast) finally slows down. Because if these continue to pass through, some may end up being rather prolific rain producers. This has happened a few times during the past five years in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. And if they don’t produce heavy rain, they can be messy and difficult to accurately predict specifics (like the system that passed through today).

Once those cease, it means the storm systems that form further north into Texas and Arkansas can take shape. Those can be the ones that – given theprevious three assumptions, tend to be the “bad systems” for the Gulf Coast and Southeast during April.

So where can all of this fail? A lot of places. That is why weather forecasting for entire months can be difficult.

If the Gulf of Mexico temperature connection isn’t as strong, cold fronts are more robust, dry lines don’t mix east, and storm systems stay in the Gulf then all of this stuff doesn’t happen.

It’s tough. Plus there are, like, infinity more variables. It isn’t as simple as just three things.

But, in general, looking at the Big Three, with two for it and one against it, that is why it is easier to lean toward a more active Spring than against an active Spring.

So what does this mean for me, Nick?

If you live along – or within 100 miles of – the Gulf Coast in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia or Florida it means you’ll like have more chances for rain that you usually would. And along the Gulf Coast in April, storm systems usually move through the area every 3-to-6 days. So a wetter-than-average month could mean an increased frequency in events, or an increased amount of precipitation during the events that happen.

As for severe weather, just keep an eye to the sky and keep tabs on your local weather forecast.

Anything more specific than that is difficult to predict with accuracy. Its like I always say with predicting the weather: the further out in time you go you have to pick between precision and accuracy. If you want precision, it won’t be as accurate. If you want accurate, it won’t be as precise.