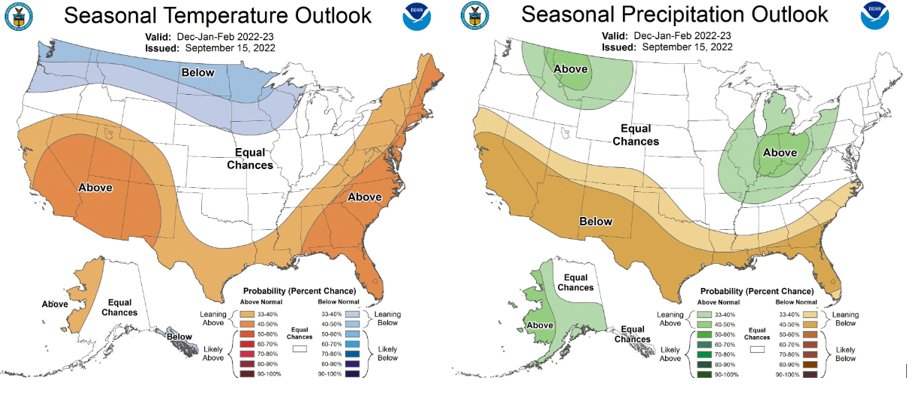

The first seasonal forecast for Winter from NOAA was released the other day. It looks very La Nina like. That is expected, though. La Nina is anticipated to continue through Fall and into Winter. With some minor changes around the edges, the expectation for the southeast is warmer than normal and drier than normal.

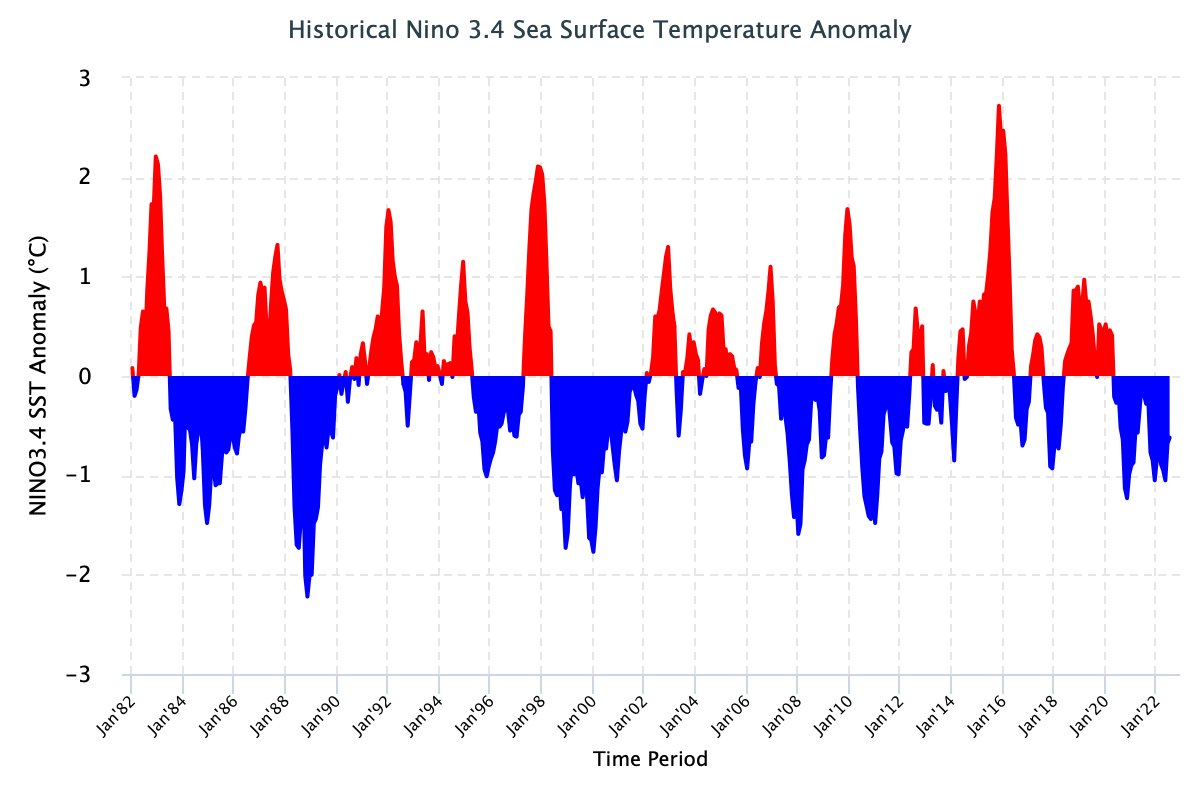

This will be the third Winter La Nina. It is rare thing. This has only happened two other times in recordable ENSO (the shorthand term for El Nino / La Nina) history. The last time was the winter of 2000-20001.

But a La Nina Winter isn’t set in stone. There is a chance we start to lean back toward nuetral. Though, that chance is pretty slim.

La Nina and the Southeast

Generally, La Nina changes how storms system line up and pass through the region. And that change, changes the temperatures, winds and precipitation across the region, too. Since this is the third La Nina in a row, there is some thought that it means the impacts might be different than the typical one-and-done La Nina.

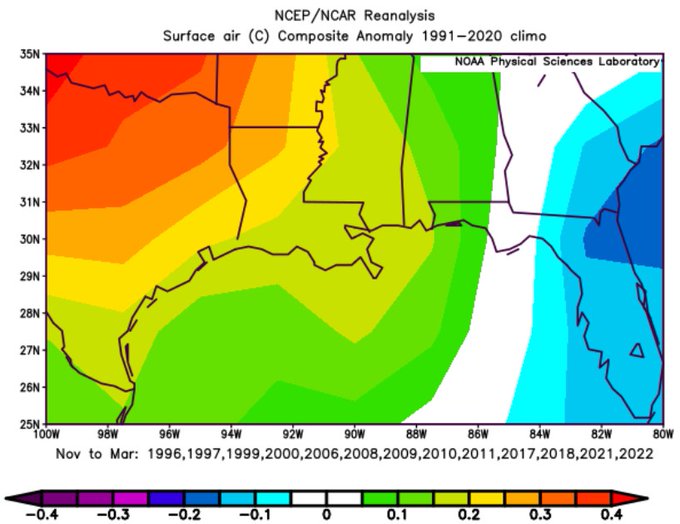

The most recent triple-dip La Nina was 2000-2001, and looking at the temperature/precipitation that Winter shows cooler temps and drier weather.

The most interesting thing about the temperature maps above is that it is much different than normal La Ninas. Normal La Nina temperatures tend to run warmer than average.

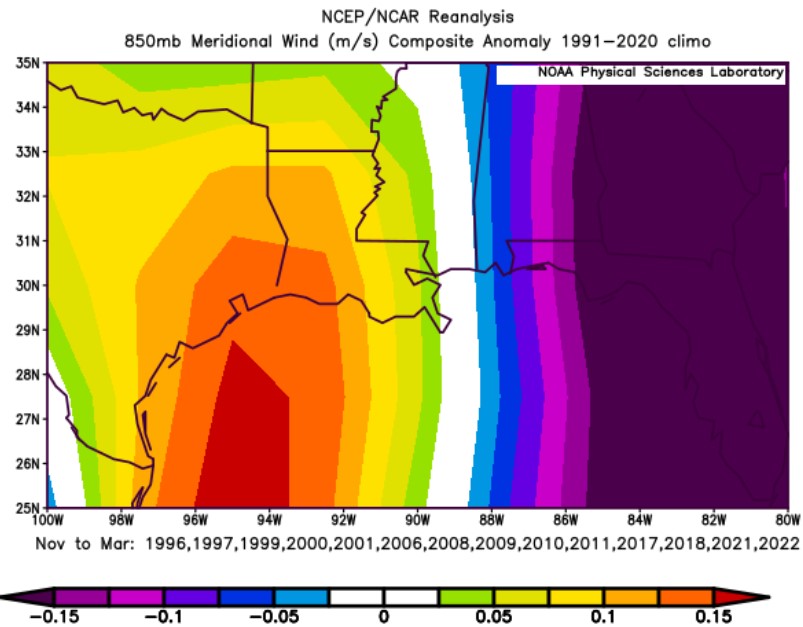

When looking at all La Ninas, part of the equation is the south-to-north wind that often blows in off the Gulf across Texas, Louisiana and western Mississippi. That south-to-north wind tends to be a warmer wind.

For that 2000-2001 winter, the wind from the south (and the north wind to the east) were both calmer.

And the wind is what plays a large role in the potential for La Nina Winters/Springs to offer better chances for severe weather.

La Nina and Severe Weather

According to research by Mark Bove, “The Ohio River Valley and Deep South see a region of statistically significant increased tornadic activity during La Niña.”

The graphic to the left shows the difference between an . ENSO-neutral year (normal) and a La Nina year (colder water). It is broken down by three-month intervals: (a) January-February-March, (b) February-March-April, (c) March-April-May, (d) April-May-June.

Notice the red blocks near us for (a), (b) but then those areas lift to our north by (c) and (d). So, despite the “generally drier than normal’ tendencies with La Nina, statistically, there is a section of the severe season that gives the Pine Belt more chances for storms, and thus, tornadoes.

That is between January and April.

Evidence for that is also supported by the historical precipitation data collected during La Nina years.

The Bottom Line

Since we only really have one example of a ‘triple dip Nina’ in the last 30 years. So we don’t have a large enough sample size to use for an accurate prediction about what that may mean. Given that, I think it is best to lean toward a “normal Nina” with the chance that we run a bit cooler than a normal Nina and a bit drier, too.

I’ll have my Winter Outlook posted as we move into October. And once we can kick Hurricane Season to the curb – or at least for the most part.