Recently across many parts of the country there have been multiple reports of people seeing “waves in the sky” during the afternoon. I’ve even posted a few pics on my facebook page and Twitter account, too! These are cool cloud formations that look like little rows of clouds migrating across the sky.

Here is an example of how they look from the ground:

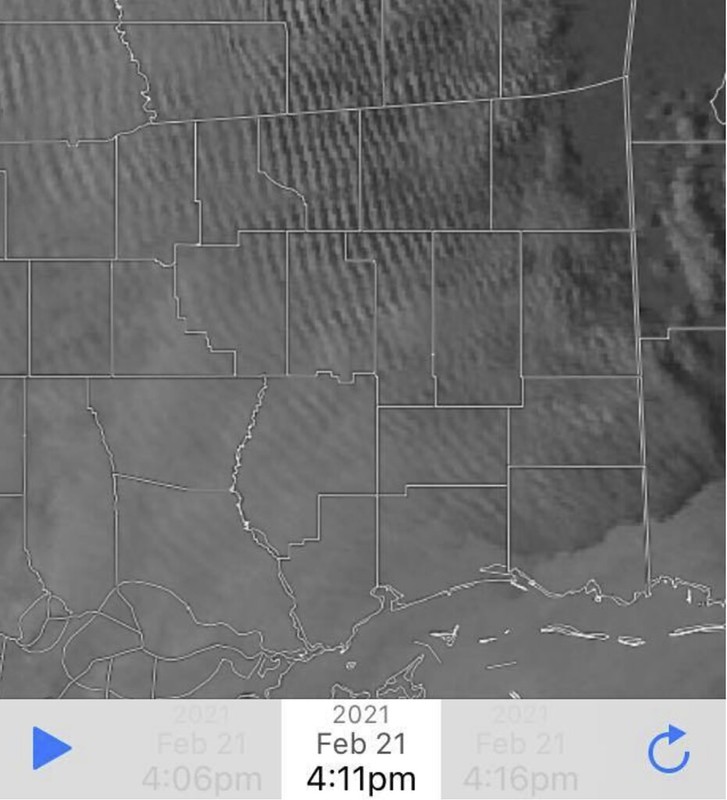

These types of clouds aren’t terribly uncommon, but it often takes a certain situation in order to develop these clouds. If you’re having a difficult time visualizing how these may look like waves, here is another wider view from above:

You can almost think of it like dropping a big rock in the center of a pond and watching the waves propagate away from the center.

Yeah! Like that! The main difference, I suppose, is the atmosphere is not a pond. And there is no giant rock to throw in it.

These types of cloud formations are known as “cloud streets” or “gravity waves” in the meteorological community, depending on their particular formation method. They have very little to do with physical streets. And not much to do with gravity, either. These are the Apple Jacks of clouds. For you 80s & 90s kids… throwback:

So, if they aren’t physical streets, and they don’t refer to actual gravity… just how do they form then, Nick?

In the words of Sheldon Lee Cooper…

Create a wave

Instead of a physical object cause ripples in the surface of a pond, the air itself is rising into a stable layer causing ripples within the atmosphere above that stable layer to form – and those ripples of rising and sinking air cause the cloud formations.

Let’s get the National Weather Service textbook definition:

To start a gravity wave, a TRIGGER mechanism must cause the air to be displaced in the vertical. Examples of trigger mechanisms that produce gravity waves are mountains and thunderstorm updrafts. To generate a gravity wave, the air must be forced to rise in STABLE air. Why? Because if air rises in unstable air it will continue to rise and will NOT create a wave pattern. If air is forced to rise up in stable air, the natural tendency will be for the air to sink back down over time (usually because the parcel forced to rise is colder than the environment).

Courtesy: weather.gov/zhu/

The momentum of the air imparted by the trigger mechanism will force the parcel to rise and the stability of the atmosphere will force the parcel of air to sink after it rises (you have now undergone the first steps into creating a wave).It is important to understand the concept of momentum. A rising or sinking air parcel will “overshoot” its equilibrium point. In a gravity wave, the parcel of air will try to remain at a location in the atmosphere where there are no forces causing it to rise or sink.

Once a force moves the parcel from its natural state of equilibrium, the parcel will try to regain its equilibrium. But in the process, it will overshoot and undershoot that natural position each time it is rising or sinking because of its own momentum.

At a sufficient distance from where the trigger mechanism caused the parcel to rise, the intensity of the gravity wave will decrease. At increasing distance, the parcel of air becomes closer to remaining at its natural state of equilibrium.In a gravity wave, the upward moving region is the most favorable region for cloud development and the sinking region favorable for clear skies.

That is why you may see rows of clouds and clear areas between the rows of clouds. A gravity wave is nothing more than a wave moving through a stable layer of the atmosphere. Thunderstorm updrafts will produce gravity waves as they try to punch into the tropopause. The tropopause represents a region of very stable air.

This stable air combined with the upward momentum of a thunderstorm updraft (trigger mechanism) will generate gravity waves within the clouds trying to push into the tropopause.

Catchin’ the waves

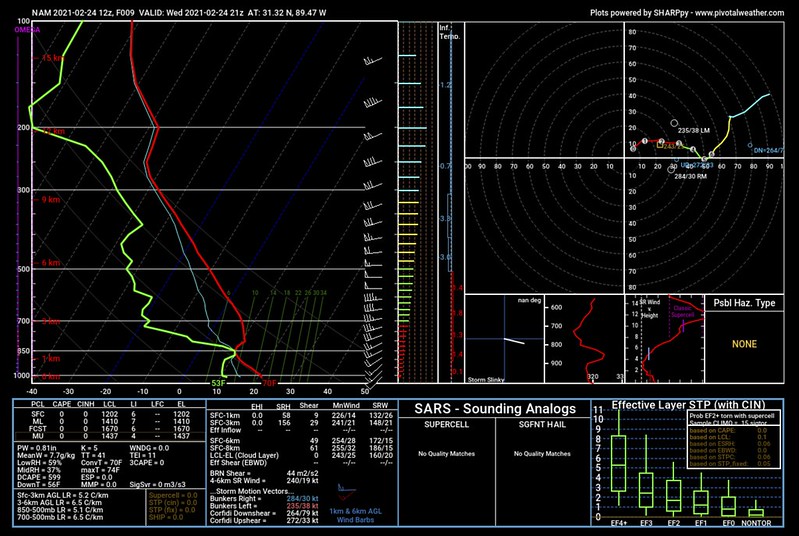

So! First, we need to see what the atmosphere looked like while this was happening. We need to make sure that what we think we are seeing is physically possible to see.

So what we need to do is look at the Skew-T chart. And look to see if we have instability (rising air) underneath a stable layer of air (inversion). And we need for that rising warm air to be moist.

Bam! We do. Now we need there to be wind in the mid-levels to carry these clouds along to give them that wavy appearance. And – BAM! – again, we do.

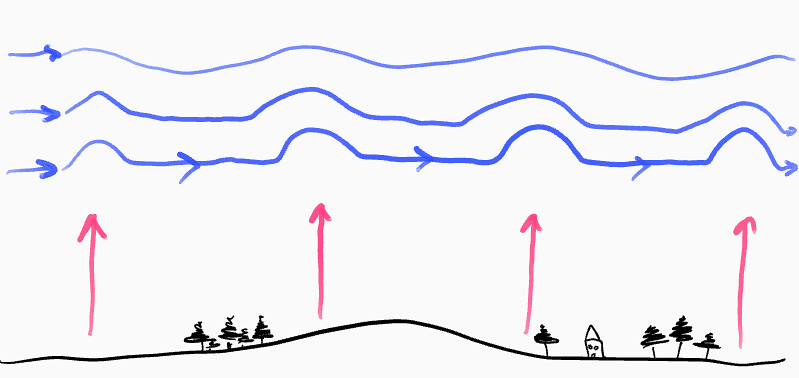

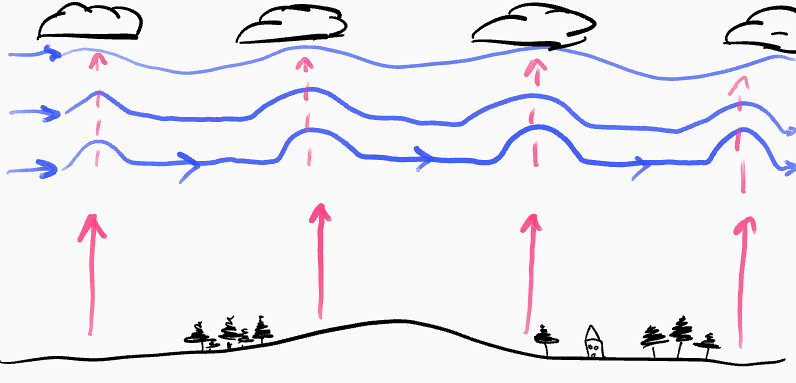

Let’s look at this very well-drawn* artists rendition of what is occurring.

You can see the single house with a few trees over the large area of land shown above. The reddish arrows are warm air rising from the surface. This warm air is rising into that stable layer of air aloft. The blue arrows are the prevailing wind in the mid-levels.

The rising air creates little bumps in the flow of the air in the mid-levels.

The bumps can be thought of like the ripples in the pond in the image above. That warm air’s pressure is not equal all the way through the column of air, though. Notice that the bumps get softer the higher up you go. By the third blue line, it looks more wavy than bumpy.

And, at the tops (crests) of those waves, there is enough lift to cool and condense out some clouds. Not big clouds. but little altocumulus clouds.

More art

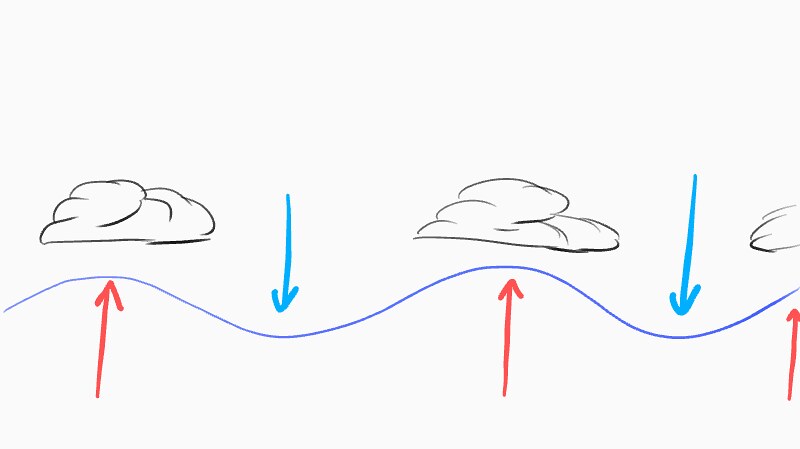

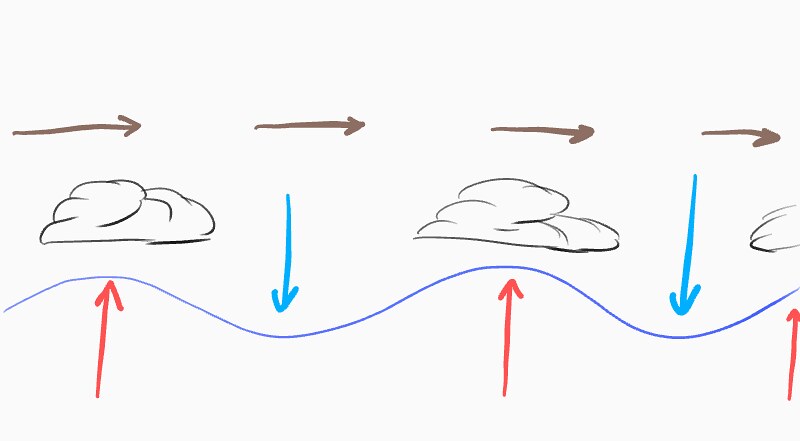

Looking closer at the clouds, using some other well-drawn* artist renditions, you can see that the air between the clouds is now sinking.

And sinking air won’t form clouds. Only rising air does that. So even as the clouds propagate in a direction, the rows of sinking air between the clouds is strong enough to overcome any additional rising air that may try to bump through.

These formations usually take a bit of time to full develop and eventually dissipate once the daytime heat comes to an end.

Pretty cool, huh? Here is a look at some Gravity Waves (among other cool things happening) in action: