As most of you guys know,I never claim to have all of the answers. But, I know there are a TON of questions floating around with these two storms and – with the reasonable rarity of having two tropical systems in the Gulf simultaneously – a lot of bad information being passed around by “unpleasant actors” with respect to what may or may not happen, I wanted to take some time to lay out what we know, don’t know, can’t know and what we want to know.

And if you stick around to the very end, I’ll fill you in on what I think may happen.

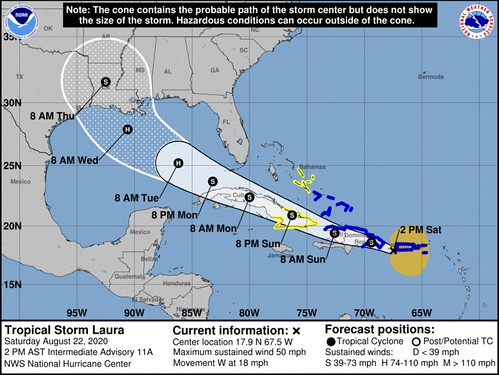

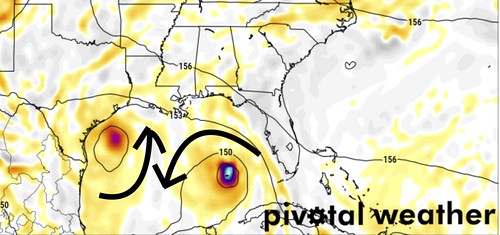

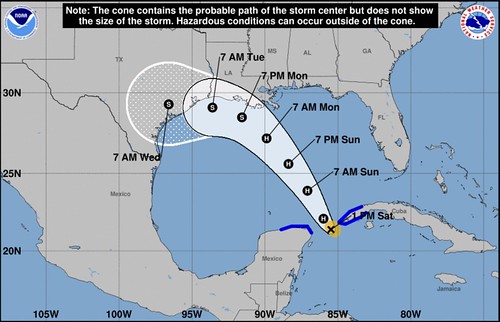

Forecasts from the NHC as of 1PM on 8/21/20

Tropical Storm Marco

Tropical Storm Laura

What we know

These won’t merge to form a super hurricane

That is not how physics works. Thankfully. More on the Fujiwhara Effect below.

The water in the Gulf is warm

Right now the water’s surface temperature is very high in the Gulf. It is running a bit above average. And while that is bad news, we really have to look under the surface to find out how much real “energy” or “food” is available for these tropical systems. Because as tropcial ystmes move across the water, they rain colder water out of the clouds and cool the water temperature at the surface. so you look under the surface to find out how deep that warm water goes.

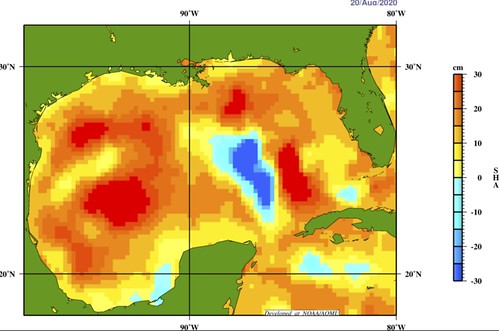

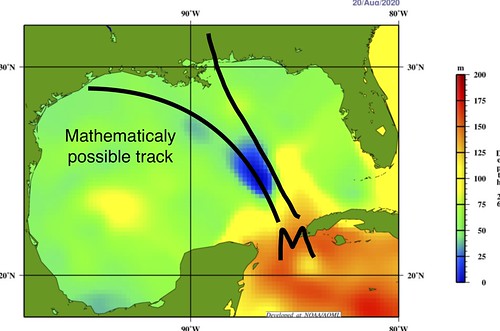

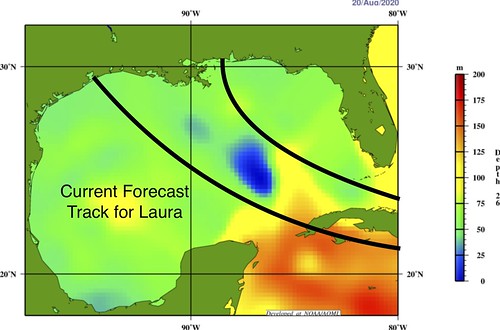

That is a simple illustration of how the temperature looks as you go down, deeper, into the ocean. And we can measure this even without dropping a thermometer into the water. We can use satellites and measure (with some incredible accuracy) the sea height.

Because water expands when it is warmed (all things do) the “sea height” can be used as a proxy to determine where the warmest water is – both on the surface and below.

The bulls-eye of blue in the central Gulf is an indication that there is an are where the water is warm at the surface, but not necessarily equally as warm very deep. So the supply of “energy” for any passing tropical storm is lower in that spot than in other places.

It doesn’t mean there is “zero” energy, but the supply is more limited.

So, what does that mean, Nick?

It means that once the first tropical system passes over that area, it will gobble up most of the available energy from the water. And if a second is to follow closely behind and travel over that same area, there would be less available energy to use for strengthening.

Laura: Islands are not good for tropical systems

Hurricanes like water. Warm water. We all know this. And hurricanes don’t like land. We all know this, too. But any tropical system hates mountains.

That is what the Dominican Republic and Haiti have an abundance of, too. Big, tall mountains. And those mountains are going to be hindering Laura’s development during the next 48 hours because it will slow down and erode away at the two circulations that are trying to get vertically stacked.

And even if the circulations can get vertically stacked, the mountains will still beat up and disrupt any circulating rainbands. And knock the systems symmetry out of alignment. And changing order and organization to disorder. This disrupts the systems ability to be the “conveyor belt of heat” that it is.

In short: mountains are bad for developing tropical systems and good for humans that don’t want tropical systems to organize and strengthen.

Marco: Dry air & shear are not good for tropical systems

There is a patch of dry and and some shear across parts of the Gulf of Mexico currently.

The above map shows an area of yellow-orange shading that indicates drier air. The yellow line denotes where the shear is located. Teh blue line is the general forecast track for Marco.

Passing through shear and dry air does not help tropical systems. A lot like passing over mountains, shear disrupts the systems ability to remain symmetric and organized. Disrupting that, slows the development of tropical systems down.

What we don’t know

A quick note to make a distinction between “knowing” and “thinking” here. There are things we don’t “know” but can still use our best math to make estimations about. A forecast, after all, is not about what we “know” but an estimation based on the best math we can use. So, in this particular post, I am going to discuss things that we don’t know with certainty.

How the two system will interact

While we can forecast it, we don’t know it for sure. Out in the open waters of the ocean, something known as the Fujiwhara Effect may come into play. That is a “little dance” so to speak, that storms goes through when they get close to each other.

A Gallery of Atmospheric Dynamics Animations

15 of 20: Co-rotating Vortices (Fujiwhara Effect)

for more info: https://t.co/GyuxwyXUtw pic.twitter.com/9ME9QPyTtR

— Mathew Barlow (@MathewABarlow) May 14, 2020

That tweet highlights how – in a perfectly modeled system – the storms will respond. The reason is the motion around one storm starts to tug at the motion around the other storm.

You can see what that look slike in the 00z GFS computer model for these two systems in the Gulf…

Notice the air wrapping around the storm on the west side (Marco) is pointing in a different direction than the storm on the east (Laura). The storms respond to this by being nudged in different directions than the storms are already traveling.

But the world isn’t a perfectly modeled system. And this isn’t in the open ocean. It is in the Gulf surrounded by land. And because the response to each other is within the vorticity of the systems, not just the clouds, so there is a large amount of “we don’t know” here.

Why?

Because looking back at that map, the orange, red and blue shaded area is vorticity. And there is a ton of it! It is not just wrapped up in those storms, its floating around all over because of the interaction of the air with the surrounding land, too.

So while we can model what this would look like in a perfectly modeled world out in the middle of the ocean, when you throw land into the equation, we don’t know exactly.

But as these two systems get closer to each other, they will still tug at one another. This may disrupt their organization, it may induce low amounts of shear to one or both, and it isn’t likely to end well for one of them. Perhaps both.

Or maybe because they are so close to land it won’t matter? We honestly aren’t sure.

how much intensification will occur

Yeah, this is a toughie. We don’t know this for certain either. And usually we don’t know this beyond about 72 hours out anyway. But with how close these two storms will be to each other, it really throws a wrench into things.

Intensification is based on a systems ability to (1) get vertically stacked, (2) get symmetric, (3) move through an area with warm water, (4) develop in an area with low wind shear, and (5) have upper-level high pressure with no dry air. There are more, but for now, we will stick with these five because they are simple and classical.

And because of the aforementioned potential Fujiwhara Effect, that may disrupt the systems ability to remain organized. That reduces out ability to accurately forecast other things when a portion of what goes into the forecast is unknown.

Plus, as we noted above dry air and shear (Marco) and mountains (Laura) are not good for tropical systems.

Where these storms will ultimately go

We don’t know this for certain, either. And I know I may sound like a broken record here, but the interaction between the two and the fallout from that makes it tough to figure out where either one will go. We can estimate, but the actual final path is not one that is easily deciphered.

The “little dance” in the perfectly modeled system discussed above does give us some insight into what may eventually occur, but further complicating things is that these storms are not moving in different directions as they pass one-another. They are moving the same way.

What we can’t know

I get a lot of questions that I, sadly, cannot answer. I wanted to pick out the top three and give some background into why.

Will this hit my city?

Because we won’t know the final path of the whole system, we have a tough time nailing down specifics to the city level. But I will say if your city is in the Forecast Cone from the National Hurricane Center, then your city has a much higher chance of being impacted. Thatemans rain, flooding, and wind are all possible.

How much wind will I see?

We can’t know that either because we don’t know the specific track. Plus we don’t know the specific intensity. Without that, we can’t know how much wind will occur at any given point.

But if your city is in the cone, and it shows a Category 1 Hurricane at that time, then prepare for wind speeds exceeding 75mph.

Will I lose power?

While I can’t know, I always tell people “plan on it” because with a landfalling tropical system, there will be rain and wind. Even in places far away from the center. So while I can’t know if a place will lose power or not, it is always best to prepare for the worst.

What we want to know

While. sure, we would love a crystal ball that would predict the future with 100-percent accuracy… here is a quick look at obtainable things we want to know…

The strength of the ridge in the Atlantic

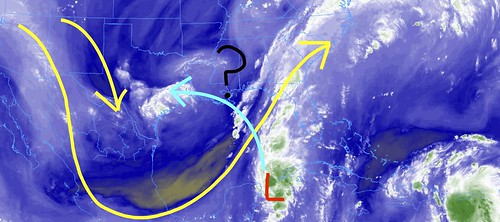

This is the thing that is “driving the bus” so to speak with Laura. This will determine just how fast and far the system makes it into the Gulf and when it decides to turn north.

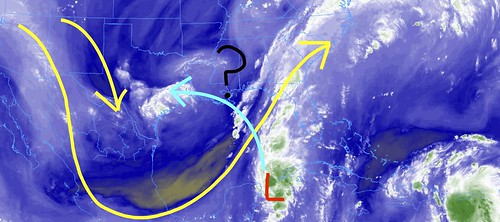

And right now, we don’t have a good feel for this due to the troughing that is in place across the Gulf.

When the trough lifts out of the Gulf

This is what is “driving the bus” with Marco. This is going to determine how far north Marco goes before pushing back west again.

How each storm will interact with the ridge building in behind the trough

The ridge of high pressure that settles in behind the trough that is leaving the Gulf will dictate where these two storms go once they get into the Gulf. The strong the ridge, the more they get pushed west. The stronger the storms, the more they’ll fight to go toward the North Pole (due to Coriolis).

It will be an interesting – albeit stressful – thing to watch.

Not a “forecast” but some ‘back of the napkin’ math

A lot of people ask me, “Yeah but, Nick, what is really going to happen?”

I rarely go against the NHC forecast because these are people with Ph.Ds and years and years and years of expertise. I’m just a guy who reads a lot. And a lot of what I read is stuff they wrote. So who am I to argue?

That said… I’m about to argue. Well, argue is too harsh a word. I’m going to explore other outcomes…

Getting back to this image showing Marco passing through a trough – with dry air – to turn west and head toward Texas. This was the forecast posted this morning, with no change made during the intermediate update.

The thought process here is – likely – that the trough weakens, Marco goes north but is then moved west by the ridge that builds in behind the trough. This forecast is a change from the previous forecasts that showed the system making a – relatively – straight-shot toward Texas.

Yellow = current upper-level winds

Green = Forecast track

Me = not confident in track vs. winds pic.twitter.com/6XrcjsRuwB

— Nick Lilja (@NickLilja) August 21, 2020

Yesterday I noted that with upper-level wind steering this thing, it is unlikely to just blow right through it and keep going. Imagine trying to navigate a canoe across a fast flowing river. What are the chances you can canoe directly – in a straight line – from one side to the other?

Very low.

And the deeper your canoe, the more difficult it is going to be to traverse the river in a straight line.

Same principle applies here.

The stronger the storm, the deeper the canoe. And as Marco continues to gain strength and develop rainbands, the more difficult time it will have moving through the trough.

So I would argue that places like Louisiana and Mississippi prepare for Marco. Potentially as a hurricane.

While it could go through “Rapid Intensification” still, that isn’t as likely given the water temperatures ahead. Take a look at the potential track – given the interaction with the trough – for Marco as it moves north. This follows the NHC track through 24 hours, but deviates further east as a potential.

But during the next 24 to 36 hours the system is going to move over an area where the water temperatures are warm at the surface, but not as warm as you move down. The image above is actually the “26C isotherm” showing how deep you can go and have the water still be 26C (79F). The 26C isotherm is a good measurement of sustaining a hurricane. If you have at least 25m of depth, a hurricane is more likely to remain a hurricane even in the face of some other limiting factors, because it will have a good source of energy to pull from.

But in this case, that is barely the case.

So, hypothesizing here, Marco could be tugged a bit more northerly than northwesterly, before making the move back to the west. But, on the back side of the trough, if it has any time to soak up some of that warmer water along the northern Gulf Coast, it may have enough time to add a bit more umph, and overcome most of the forcing from the ridge to the north.

Remains to be seen, specifically, but given the overall setup, is a reasonable hypothesis.

As for Laura, this is more of a wildcard. Because of Marco cools the surface waters enough in the Gulf, the upwelling of warmer water below may not have enough time to fully replenish the bathwater to the surface before Laura passes.

And while Laura will have a more favorable environment with the trough gone, it may not have as much warm water to feed off of. Take a look at the forecast track placed over the same 26C Isotherm map.

Notice there isn’t as much warm water to depth.

This storm’s journey is going to be dependent on the ridge building in from the north and where Marco is when it finally gets into the Gulf.

If we assume Marco make a trek north and then back west during the next 48 hours, that puts Laura near Cuba as Marco is close to making landfall. That puts the storms about 600-ish miles apart. Close enough to feel a bit of a tug from each other. As noted by Philippe Papin:

Oh wow I can’t believe that #Hilary & #Irwin example is already more than 3 years old! Maybe there will be a GFS fcast w/ #TD14 & #Laura where I can attempt to update these graphics for a current forecast.

In the meantime here is my emoji form attempt 😅

↙️⬅️🌀

⬇️❌⬆️

🌀➡️↗️— Philippe Papin (@pppapin) August 22, 2020

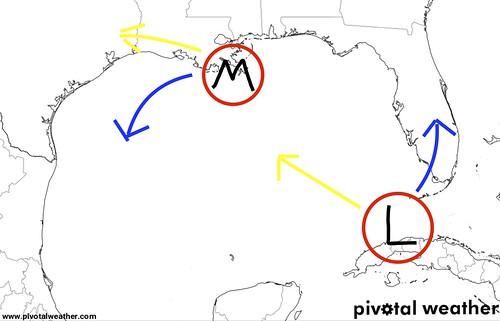

So, you would see Marco “deflect” to the left of its intended path and Laura deflect to the right of its intended path.

In the above image, the yellow line indicates the intended path, and the blue indicate the deflection.

How much deflection?

No idea. That goes back to the parts above where due to land interaction we cannot estimate – accurately – what will happen.

But that deflection does increase the risk of landfall for place like Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Yes, we could have two landfalls in Louisiana in the span of 72 hours. Like?y not really. Possible? Yes.

And to even say it is “possible” is just crazy to think.

But, truly, Laura is a little too far out to be trying to make prediction about its final track. Just know that it may ride of the right side of the cone. Or the forecast cone may shift a bit to the right, given the potential interaction.

The Bottom Line

The above discussion is not the forecast. It is an exploration of potential scenarios given the atmospheric setup. The current forecast calls for Marco to head toward Louisiana and Texas, and Laura to move toward Louisiana and Mississippi.

But that may change. And will likely change. Please keep tabs on the forecast.

But check your Hurricane Preparedness Kit now. Check your Hurricane Plan now. Do you have enough supplies to last a few days without power or water? Do you have enough medicine to get you through? Are all of the shrubs and trees trimmed near your house? Can heavy rain get moved away from your home to reduce the risk of flooding?

Prepare your home now for the potential. If nothing happens? Great! You were prepared. But you don’t want to be caught unprepared if something does happen.