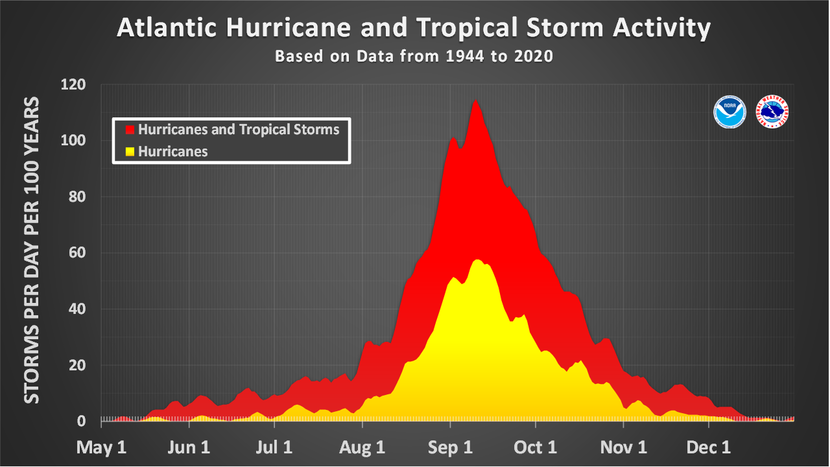

Good morning, folks! The Atlantic Hurricane Season began earlier this month – it was the first of which to not feature a pre-season tropical system since 2014. The only notable tropical system so far this season has been Potential Tropical Cyclone One / Tropical Storm Alex, which brought flooding rains and gusty winds to southern Florida earlier this month. Aside from this relatively weak tropical cyclone, the Atlantic Basin has been quiet thus far – which is to be expected as the Atlantic Hurricane Season doesn’t really begin to ramp up until August.

That doesn’t mean that things have been quiet everywhere… In the Eastern Pacific, where their hurricane season runs from May 15th to November 30th, there have already been three designated tropical cyclones: Hurricane Agatha, Hurricane Blas, and the ongoing Tropical Storm Celia.

According to the National Hurricane Center, Tropical Storm Celia is forecast to strengthen into a hurricane later this week. Much like Hurricane Blas before her, Celia doesn’t pose much of a threat to land at this time apart from the Revillagigedo Islands of Mexico, a common hurricane-target about 300 miles south of Cabo San Lucas.

Current Conditions in the Tropics

While the tropical Atlantic is mostly quiet, there are still a few things that we’re keeping our eyes on. From right to left on the image above,

System 1 is Tropical Storm Celia in the Eastern Pacific,

System 2 is a weak tropical wave just west of the Lesser Antilles,

System 3 is some convection associated with a weak African easterly wave, and finally,

System 4 is some broad convection associated with an emerging African easterly wave off the coast of Senegal.

As Celia is in the East Pacific Basin, we won’t focus much on her for this update.

Aside from a pre-existing disturbance, some of the main ingredients for tropical cyclogenesis – the formation of tropical cyclones – are warm ocean temperatures, weak wind shear, and sufficiently moist mid-level air. So let’s take a peek at some data to see what these disturbances are working with…

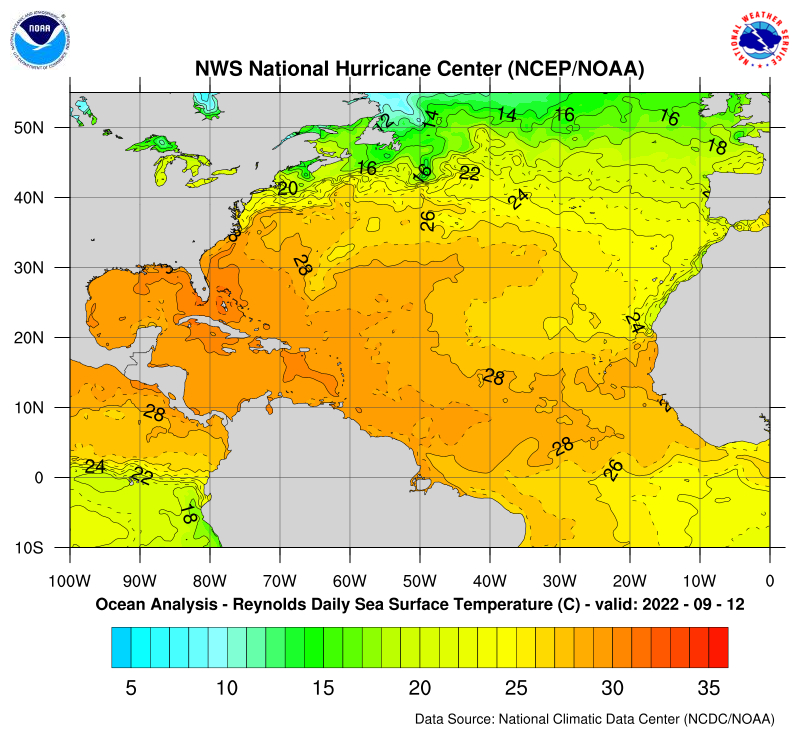

Generally speaking, tropical cyclones need sea surface temperatures to be greater than 26 C (80 F) to develop. This is necessary because warm ocean temperatures provide the energy for a disturbance to grow into a strong tropical cyclone. Referencing the left-hand image above, sea surface temperatures are above 26 C for all of the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and most of the Eastern Atlantic between 15N and the equator. The right-hand image shows the sea surface temperature anomaly, which shows about average temperatures for the southern Gulf of Mexico and most of the Caribbean, but above average temperatures for most of the Eastern Atlantic.

Another essential ingredient for the development of tropical cyclones is weak wind shear. Taking a look at the image above, it certainly doesn’t seem like there’s a lot to work with here. Strong wind shear is detrimental to a developing tropical cyclone because it disrupts the vertical structure of the storm; strong shear can also help drier air work its way into a system, which can limit the formation of thunderstorms around the center – thus weakening the tropical cyclone. Generally speaking, wind shear less than 20 knots allows for a tropical cyclone to intensify. As of now, the only place where sea surface temperatures are warm enough and where wind shear is low enough is along a narrow corridor circled above.

It is also interesting to note the high shear in the Eastern Caribbean, where System 2 is located. Throughout the day on Tuesday, the convection associated with System 2 has diminished, likely due to the increase in wind shear. As this system will continue to move into a region of even stronger shear, tropical cyclogenesis is very unlikely.

Lastly, it is also important to identify where dry air is. Dry air can inhibit the development of a tropical cyclone as it makes it more difficult for thunderstorms to form. In the image above, the brown colors show a large region of dry air over most of the Eastern Atlantic, with pockets of relatively moist air courtesy of the convection associated with Systems 3 and 4.

So with this quick current condition analysis we’ve determined that the only location where there are pre-existing disturbances, warm sea surface temperatures, weak wind shear and sufficiently moist mid-levels is the narrow corridor in the Eastern Atlantic where we’ve highlighted systems 3 and 4. Now we can look at how the conditions are likely to develop based on model data to determine if these systems have the potential to develop further.

What the future holds…

Taking a look at the next few days, we’ll start to see some changes in the Tropical Atlantic.

The first significant change is the notable decrease in wind shear off the coast of West Africa. As an emerging African easterly wave enters the region, the decreased shear will make the environment around the system more conducive for tropical cyclogenesis.

By Friday evening, the individual moisture signals from Systems 3 and 4 have merged, with another disturbance emerging from West Africa helping to inject additional moisture into the circle region above. By the end of the week, the ECMWF is showing a tropical wave entering a favorable environment for the development of tropical cyclones.

In fact, both the European ECMWF model and the Canadian GEM model depict the development of a weak tropical cyclone from the disturbance moving off of the West African coast in the southern Caribbean by the middle of next week. It’s worth noting, however, that not all of the global models are on board with this solution.

The American GFS model, which is notorious for spinning up fantasy tropical cyclones hundreds of hours out, uncharacteristically only shows weak and disorganized upper-level cyclonic vorticity associated with an elongated region of showers and thunderstorms in the southern Caribbean.

One important take-away is that model error this far out is significant, and the only way to achieve more confidence with a forecast is to wait until more is known about the system emerging from West Africa. On the other hand, because we know the ingredients for tropical cyclogenesis will be place, these signals from global models showing the formation of a weak tropical system need to be watched closely.

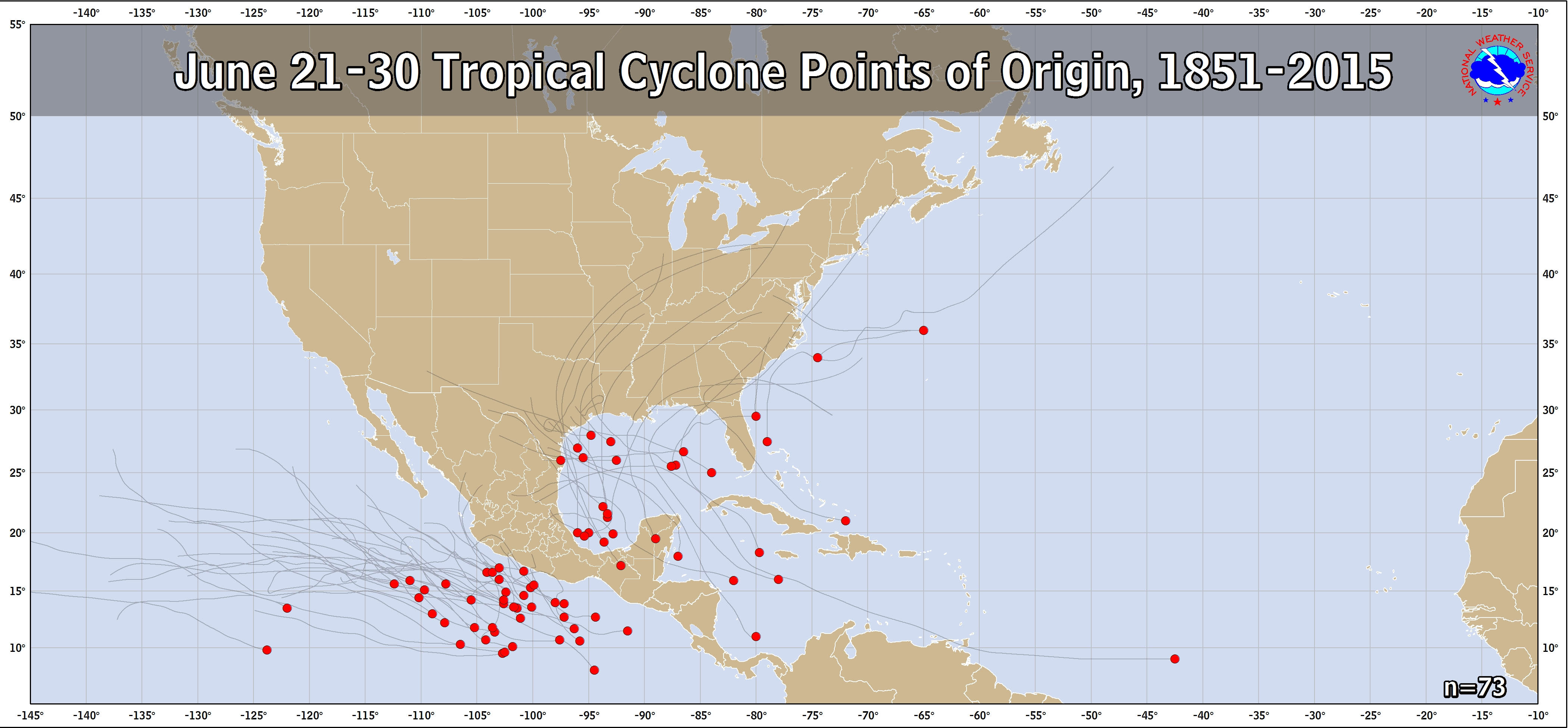

After all, although the Gulf of Mexico is climatologically favored for the development of tropical cyclones during this time of year, there have been a number of storms that have developed in the southwestern Caribbean. While it is unusually early for an African easterly wave to develop into a tropical cyclone, this system will be something to keep an eye on in the coming days.