Some people balk at even the mention of climate change. They scoff at people who are concerned about a warming earth. And some even argue about cycles that are easily refuted by an avalanche of evidence.

This isn’t for those folks. And that is fine. Because I understand that you can’t change every person’s willingness to trust experts.

For everyone else, though, the good thing about facts is that it doesn’t matter what someone’s opinion is… a fact is still a fact. Evidence is still evidence. Statistics may lie, but math does not.

For south Mississippi, climate change doesn’t mean the same thing that it means in Reno, Nevada or Burlington, Vermont. A lot like weather, in a way, the consequences of our changing climate are different for different places.

When Physics is our friend

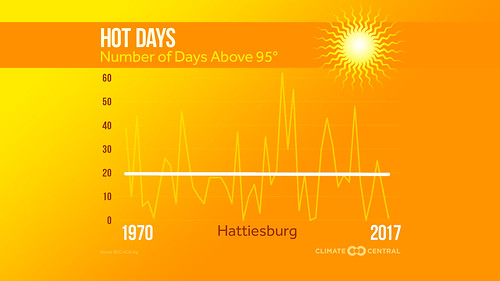

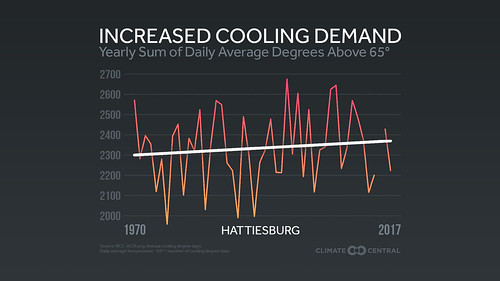

The above graph shows that extreme afternoon heat isn’t changing in south Mississippi. And that is true of a lot of places in the southeast. The area is lucky, as it is located near the Gulf of Mexico. The big bowl of warm water to the south helps regulate local temperatures by aiding in the development of afternoon storms. Oh, and by just regular ole physics.

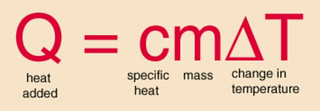

The equation pulled from the Georgia State physics page shows why having all of that water around is helpful. As stated on the page, “The specific heat of water is 1 calorie/gram °C = 4.186 joule/gram °C which is higher than any other common substance. As a result, water plays a very important role in temperature regulation.”

That basically means, because water has a higher specific heat it takes more energy to change its temperature. So, unless you pump in a bunch of energy, the temperature is going to stay the same.

And because the air above water is always trying to reach an “equilibrium of water vapor” per a given temperature, the warmer it is, the more water vapor can be evaporated. And the more water vapor in the air, the harder it becomes to change the air temperature.

So, the more water you around you, the fewer fluctuations in the air temperature.

But that can also create a problem.

When Physics is not our friend

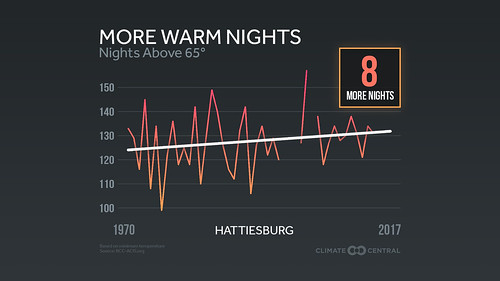

Once that air is warmed, it doesn’t want to cool down, either.

And as the planet gets warmer, even by fractions of a degree, it becomes tougher to cool down that air overnight because the oceans are that much warmer pumping the air full of water vapor that doesn’t cool down as quickly either.

Then there is this:

The top-3 meters of the ocean hold as much heat as the entire atmosphere – Dr. Margaret Leinen, @Scripps_Ocean #awf2018

— Chris “Skedaddling” Vagasky (@COweatherman) April 24, 2018

That is pretty incredible.

So what does this Physics stuff mean for me?

I’m not here to get all Doomsday on everyone. But there are some short-term, real-world, you’re-going-to-notice-this type of stuff that will happen.

First, it’ll cost you more to run the air conditioning.

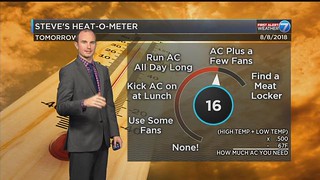

The graphic here is based off of the same principle that I used to create the Heat-O-Meter featured on the evening news.

Cooling Degree Days are a measure of how many degrees, per day, the average temperature is above 65 degrees (for my Heat-O-Meter, I used 67, because we are a bit more used to the heat and can handle a few extra degrees). The thought is that if the average temperature is 65, that could mean a high of 75 and a low of 55 – no need to use the AC. For every degree you go up, you may need a bit of AC. So a 76 high and 56 low is an average temperature of 66 degrees. One cooling degree day.

Cooling Degree Days are a measure of how many degrees, per day, the average temperature is above 65 degrees (for my Heat-O-Meter, I used 67, because we are a bit more used to the heat and can handle a few extra degrees). The thought is that if the average temperature is 65, that could mean a high of 75 and a low of 55 – no need to use the AC. For every degree you go up, you may need a bit of AC. So a 76 high and 56 low is an average temperature of 66 degrees. One cooling degree day.

The graphic showing “Cooling Demand” works off of that principle. We have increased our cooling degree days almost 100 per year.

That isn’t crazy, but it is definitely considerable.

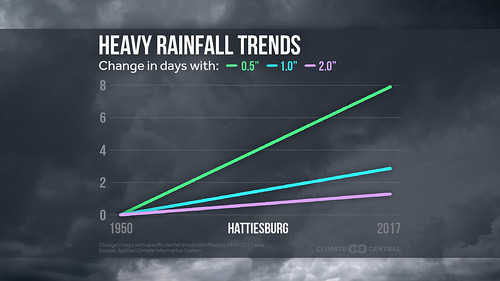

Second, when it rains, it’ll pour.

Evidence for this has been realized all over the globe. And it is something that makes sense when you think back to that equilibrium topic above. The warmer it is, the more water vapor that will evaporate. The more water vapor evaporated, the more that can condense into a cloud and eventually precipitate out of it.

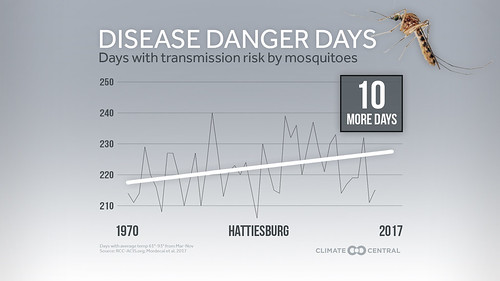

Third, mosquitos become more than just a nuisance.

This one surprised me. Turns out that new research from Stanford University found that the species of mosquitos that carry some of the bad diseases (Zika, for example) tend to be more active between certain temperatures. The study looked at data from 2013 to 2016, so the sample size isn’t huge, but given the research was done on a global scale, that does help give credence to the findings. The authors found, “human case data both show that transmission occurs between 18–34°C with maximal transmission occurring in a range from 26–29°C.”

Converted to Fahrenheit, that maximal number is between 79 to 84 degrees. temperatures, that in south Mississippi, are experienced more often in a warmer climate.

Quick Notes

Basically, a changing climate means that a warmer – even slightly – climate will introduce a higher demand for AC, heavier rain episodes with more flooding, and possibly more diseases transmissions via mosquitos.

The best news, is that you can help slow down the rate of warming by simple steps like recycling, not driving you car as much, and turning off lights when you leave a room. Saving energy, saves greenhouse gases from entering the atmosphere. And that can help keep our planet stay cooler – both literally and figuratively.