There are plenty of once-in-a-lifetime weather events for people living in south Mississippi. Usually it is things like tornadoes and hurricanes, though. In recent years, the December 8th, 2017 snowfall could be put on the once-in-a-lifetime event list, too.

But when it comes to once-in-a-lifetime thunderstorms, most people would assume the outcome to be catastrophic.

That is not the case here.

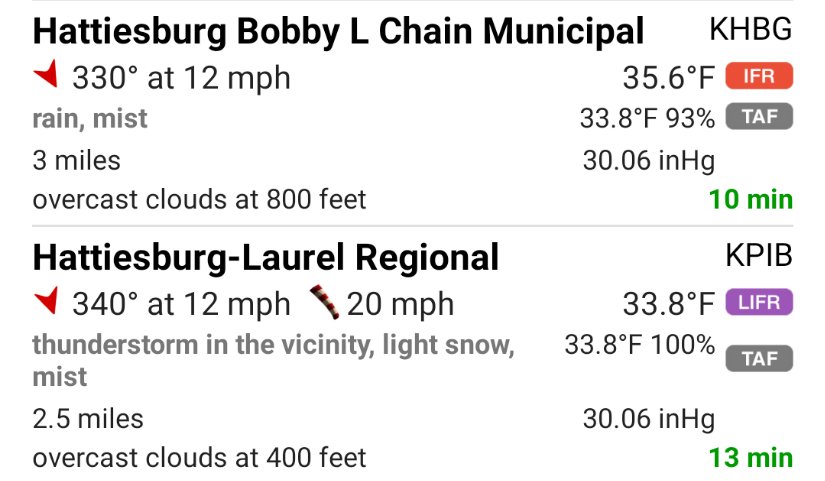

Instead, these were the coldest thunderstorms of pure regular rain that are physically possible. Seriously. During the evening on February 17th, 2021, parts of South Mississippi experienced thunderstorms in temperatures between 33 and 35 degrees.

That may say “light snow” at KPIB but I can assure you that no snow was falling. I was about two miles down the road and it was all rain. With thunder and lightning. And 33.8 degrees. Unreal.

What’s so special, Nick? It thundersnows!

Sure does! And I recently broke down Thundersleet, too! But that is frozen precipitation. And all we had was full-on liquid stuff. Jim Cantore can get excited about the rarity of thundersnow. But everyone in South Mississippi probably saw something he will never experience.

Because to get a thunderstorm with just rain – and nothing frozen – at temperatures that cold takes a very unique – and very particular – set of events in order to occur.

What events? I’m so glad you asked!

Firstly…

It takes cold air at the surface, but cold air that is not below freezing, because then it would be “Freezing rain” and not just rain. So the temperature needs to be above 32, but below 36.

Secondly…

The surface humidity has to be above 90-percent, or else evaporative cooling is likely going to cool the temperature down as the rain falls. And the air may dip below freezing.

This is something we saw earlier in the day along the I-20 corridor. Places were at 33 and 34 degrees… but drier with lower humidity. As the rain began to fall, it evaporatively cooled the air temperature to at or below freezing and rain turned to freezing rain, and water started to stick as ice.

Thirdly…

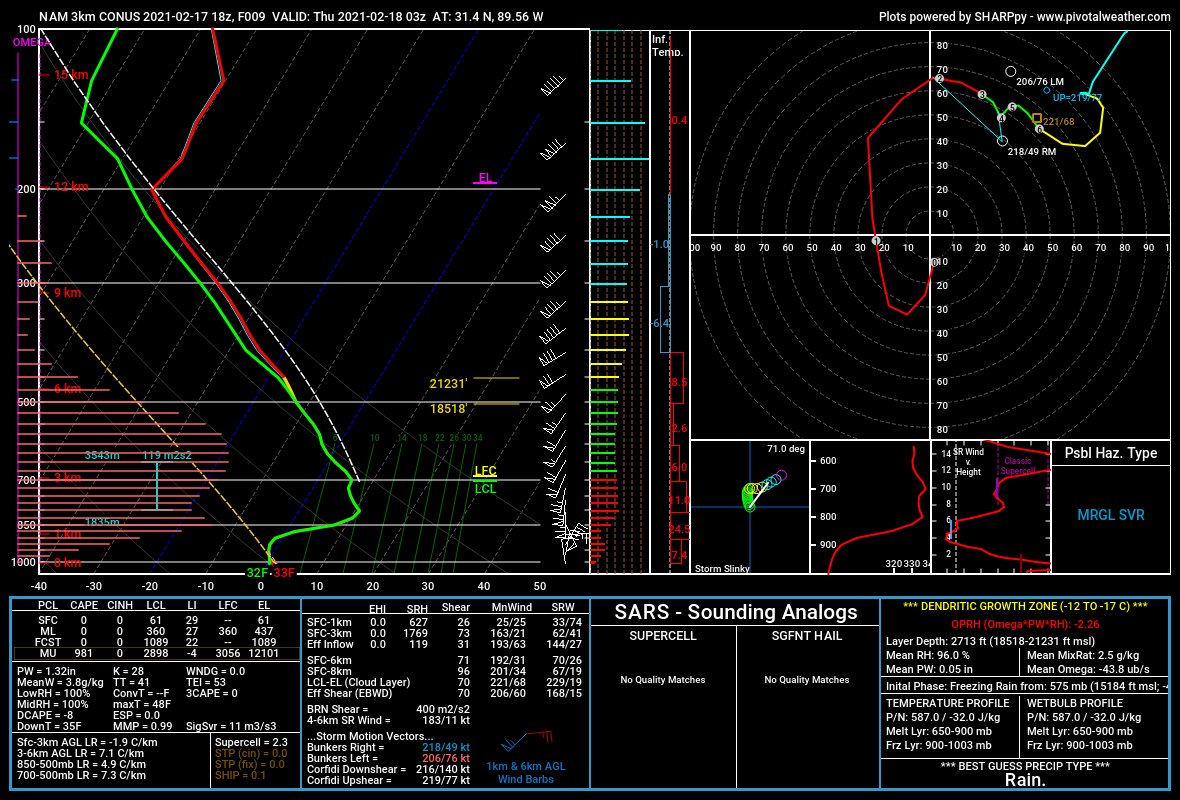

There has to be an inversion that is particularly stout – greater than 8 degrees Celsius. Since the surface temperature is near freezing, this also has to be a deep inversion above a shallow layer of cold air. One that is warm enough to melt any frozen precipitation that forms aloft. And also close enough to the ground so that as you move up from the surface you reach the inversion before the temperature falls below freezing.

Fourthly….

Along the same lines, the shallow layer of cold air can’t be more than half a kilometer deep due to what is known as the lapse rate. A lapse rate is the rate at which the atmosphere cools as you move up. The atmosphere naturally cools at about 9.8-degrees Celsius per kilometer if the air is not saturated, it is known as the dry adiabatic lapse rate. When the air is saturated, it is known as the moist adiabatic lapse rate. That is about 5-degrees Celsius per kilometer.

Either way, your shallow cold-air-layer can’t be very deep, because you start to naturally cool down as you gain elevation. And if the ground temperature is 33-degrees, you can’t move up very high before you get to a point where you are below freezing.

Fifthly…

Seriously, there is a fifthly. Fifthly! There has to be instability above the inversion. That is to say, the inversion has to have a warm-enough layer of air, underneath cold-enough air above it. And that difference between the inversion and, say, 500mb, needs to be equal to the difference you would see between 850mb and 500mb on a day with the threat for regular storms.

Sixthly…

Honestly, I don’t even know if ‘sixthly’ is a word. But sixthly!There has to be enough wind shear within the atmosphere to organize the storm and differentiate the rain droplets. Without this, there can’t be the build-up of an electrical charge, and there won’t be any lightning.

Seventhly…

Lucky number seventhly! The mid-levels of the atmosphere have to be very moist. If too much dry air gets into the mid-levels the storm will start to produce hailstones that are too big to melt before they hit the ground. So the mid-levels have to be pretty moist.

South Mississippi had all of those things

Seriously. And that is a pretty incredibly feat. The other cool thing (pun totally intended) about the inversion is that it made the thunder really – REALLY! – loud. Because the shockwave of the sound would bounce off the warmer layer of air and rumble around like crazy.

Okay, let’s take a look at the sounding.

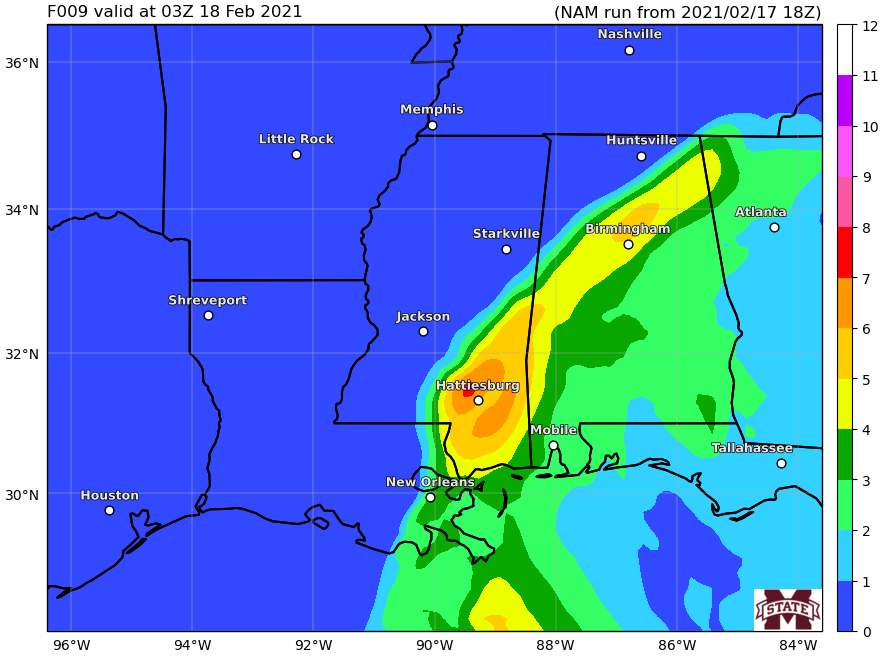

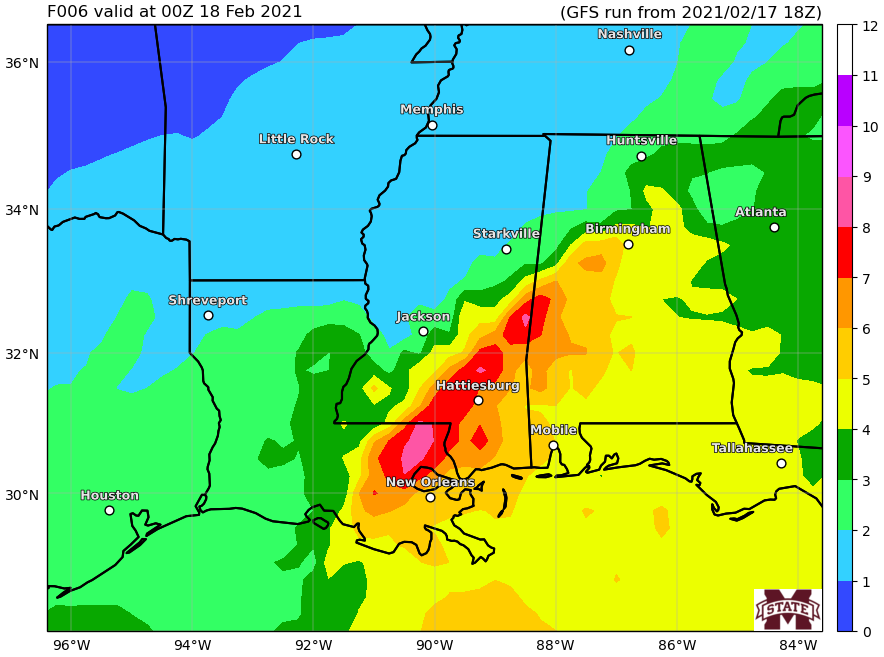

The Karrie Meter, even with the very cold temperatures, was still kicking out numbers above a “6” across the area.

That is the indication of a reasonably potent severe weather setup – above the inversion. To give you an idea about what it may have looked like on a typical severe weather day in the Winter if it were actually 65 degrees….

That is a big plot of 7 with some splotches of 8 mixed in. Yikes.

But all of this was parked on top of air that was hovering just above freezing. And that air that was just above freezing was only in the lowest 1500ft in the atmosphere. The rest of the 38,000ft of the troposphere, it was Thunderstorm City. It looked like Severe Weather Central! Riding the Tornado Express to Destruction Town.

But that last 1500ft, was barely above freezing. And because of that, no severe weather. No tornadoes.

Because because of all of the stuff happening aloft, there was still lightning and thunder.

What if I missed it, Nick? What are the chances it happens again?

I wouldn’t even know how to put a number to the chance that this ever happens again. The likelihood that is happened a first time are nearly indistinguishable from zero. To happen a second time? Within a person’s lifetime? In the same place? At an hour when people are up and alert?

No idea.

But if you did see it, you witnessed something truly special. And something that will likely not happen again in your lifetime.

One thought on “Wednesday’s storms in South Mississippi were a once-in-a-lifetime event”

Comments are closed.