Hurricane Dorian is in the process of re-shaping some of the islands of the Bahamas. The destruction it will cause is unimaginable.

So why weren’t the forecasts a few days ago as good as the forecasts today?

How are meteorologists so sure that Dorian will make the turn?

And why are all the spaghetti models so close together today and not last week?

These are all great questions.

Forecasts are based on available data

When storms are just starting to form out in the Atlantic, there aren’t many weather readings available to put into the weather models. And, therefore, when the models are run, they are missing key data to accurately predict where a tropical system is going.

The NWS releases weather balloons every day, once in the morning and once at night to collect specific information about the atmosphere. The balloons are sent up at specific locations daily.

The information collected by the weather balloons is put into the modelling as the ‘initialization’ data. The idea is, you want to get a good picture of what the atmosphere looks like right now in order to make an accurate prediction about what it may look like in the future.

Because models are run every six hours, the idea is that the morning models and the evening models (12z and 00z) will be ‘more accurate’ because they are ‘initializing’ with the most accurate look at the atmosphere.

Sometimes they will release balloons in the middle of the day, too. And other times they’ll do it in the middle of the night.

Recently, the NWS has been launching extra balloons (as seen above). That way, the other models (6z and 18z) can also be more accurate.

But what about the balloons that are released over the ocean?

Well, notice that the balloons aren’t being sent up way out in the ocean, or even at the islands in the Caribbean. This is for a lot of reasons. The top one is likely funding.

But I won’t get into that problem here!

So, if there are no weather balloons, and no accurate data to pull from, the atmospheric conditions in those areas has to be estimated based on satellite data and extrapolation from other modeling.

That can create a big problem. Starting a weather model from estimated / extrapolated data can insert errors in the predictions. This happens because the weather models don’t have an accurate look at what the actual atmosphere looks like right now.

Imagine if I looked at the temperature from a local airport and saw that it was 92 at 2pm. I then gave a forecast high for your town, on the other side of the county, of 95 degrees.

But it was already 96.

The bad forecast isn’t because I’m a bad meteorologist or a computer is bad at predicting. The error occurred due to a lack of actual data for your particular spot.

That is what happens early on with tropical systems.

The NWS and the NHC lack actual hard data on the particular spot where the tropical system actually is. So the forecast for that particular storm is going to be inherently flawed and imperfect.

Hurricane Hunters replace the missing data

The NHC resolves this missing data issue by sending out Hurricane Hunters to get data in and around the tropical system.

The data that is collected is then inserted into the modeling where previous estimations were made. That increases the accuracy of the model. This is done every six hours, every day, until the tropical system makes landfall or is no longer a threat to the public.

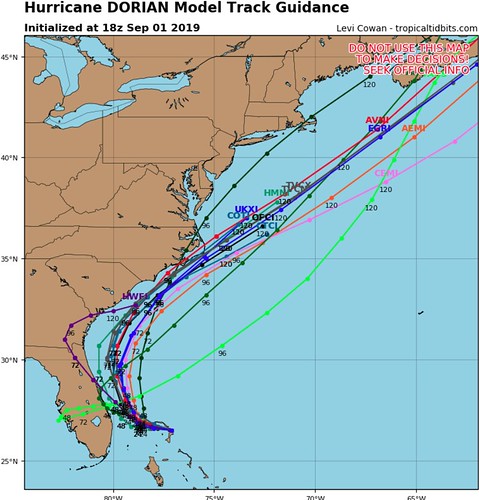

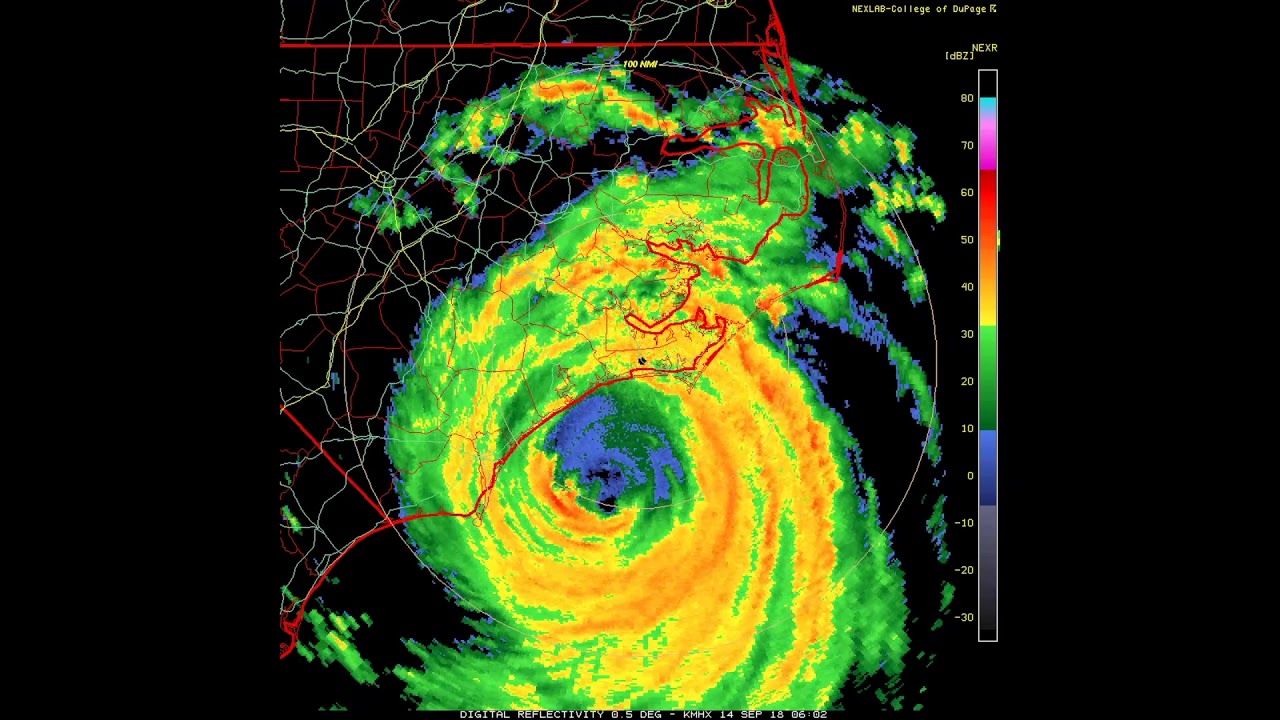

That is why the spaghetti models today look like this:

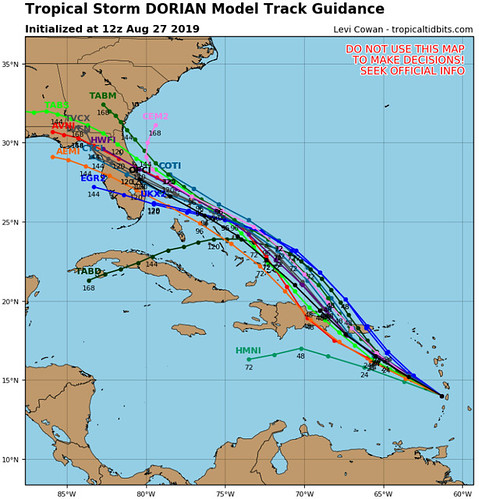

Where a few days ago there were still many outliers:

And even then, despite some wiggling, the track guidance wasn’t bad.

How can I trust the turn north – or any turn at all?

Once these systems are developed and properly sampled (that is the fancy weather way of saying the Hurricane Hunters have been flying around them for a while) the models tend to do a pretty decent job, albeit not perfect, at offering good guidance to base a forecast.

The meteorologists as the National Hurricane Center have years and years of experience and some of the best technology, too. While they aren’t perfect, they do a great job.

But at first they said it was going to be a tropical storm, now it is a Category 5 Hurricane… what gives?

A lot gives, sadly. Intensity forecasting is still something that meteorologists aren’t great at. That said, part of the slow increase in potential strength at landfall has to do with social science and psychology.

If someone told you that in a week a Category 5 was going to make landfall in Biloxi. Then two days before landfall they said it was going to be a Category 2 in Pascagoula, you may not prepare quite as well since it ‘wasn’t going to be as bad’ after all. Its okay. It is human nature. Psychology doesn’t discriminate. We would all be guilty of this. It is known as Anchor Bias.

But, if I told you that in a week a Tropical Storm was going to be in Biloxi and then two days before I told you a Category 2 was going to be in Pascagoula, you may continue to prepare normally. Because the threat is the same the whole time.

A good example of this was with Hurricane Florence.

Originally forecast to be a Category 4 near landfall, it eventually weakened to a Category 1. People took it less seriously. And some buildings were damaged, people were injured – or worse – because of that.

The NHC (and the SPC) have done this. Because they don’t want to have to pull back a forecast slightly after the models go too high with guidance. Or change completely. So the meteorologists are more likely to slowly ‘build up’ to the actual forecast.

Of note, this is something I will do also – with every forecast.

The Bottom Line

This is why it is important to keep checking back with forecasts for tropical systems. This is why the forecasts can change – sometimes drastically – between when a system first forms and a day or two later.

The original forecast was based on a complete computer estimate for the atmosphere in and around the system. But once the Hurricane Hunters check it out, that data is added to the modeling and the forecast becomes more accurate (though, not perfect).